This post is part our series providing resources relating to the Balfour Declaration and it will be permanently available in the Library section on the menu bar above.

The following lecture was given by the British historian Sir Martin Gilbert – Winston Churchill’s official biographer – at the Foreign Office in London in October 2007.

On 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. In the early months of the war, as the fighting at sea intensified, Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, faced a growing shortage of acetone, the solvent used in making cordite: the essential naval explosive. Through the head of the powder department at the Admiralty, Sir Frederic Nathan, a Jewish chemical engineer, Churchill approached Chaim Weizmann, who for the past decade had been working at Manchester University (he and Churchill had shared a platform in 1905 to protest against the most recent Russian pogroms).

Weizmann later recalled their meeting at the Admiralty: ‘Almost his first words were: “Well, Dr. Weizmann, we need thirty thousand tons of acetone. Can you make it?” I was so terrified by this lordly request that I almost turned tail.”’ But Weizmann did answer, telling Churchill: ‘So far I have succeeded in making a few hundred cubic centimetres of acetone at a time by the fermentation process. … if I were somehow able to produce a ton of acetone, I would be able to multiply that by any factor you chose … I was given carte blanche by Mr Churchill and the department, and I took upon myself a task which was to tax all my energies for the next two years, and which was to have consequences which I did not foresee’.

Those consequences were the support shown by Churchill’s successor at the Admiralty, Arthur Balfour, whom Weizmann won over to the prospect of British support for a Jewish National Home in Palestine once Turkey had been defeated.

In July 1917 the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, appointed Churchill to be Minister of Munitions. Among the senior civil servants on Churchill’s Munitions Council was Sir Frederic Nathan, then Director of Propellant Supplies, under whom Weizmann was working. In early 1917, Weizmann concluded his work on acetone, successfully, with the result that Britain had all the cordite explosive propellant needed for the British war effort.

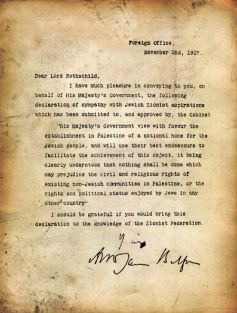

Within a year, on 2 November 1917, A.J. Balfour, Foreign Secretary in Lloyd George’s government, sent his epoch-making letter to Lord Rothschild, for the attention of the Zionist Federation, stating: ‘His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.’

The War Cabinet hoped that, inspired by the promise of a national home in Palestine, Russian Jews would encourage Russia, then in the throws of an anti-war revolution, to stay in the war; and at the same time, that American Jewry would be stimulated to accelerate the military participation of the United States – already at war, but not yet active on the battlefield. On 24 October 1917, Balfour had told the War Cabinet: ‘The vast majority of Jews in Russia and America, as, indeed, all over the world, now appeared to be favourable to Zionism. If we could make a declaration favourable to such an ideal, we should be able to carry on extremely useful propaganda both in Russia and America.’ On November 1, Ronald Graham, a senior Foreign Office official – writing a few rooms away from where we are sitting tonight – urged the immediate publication of the Balfour Declaration in order to influence the Jews of Russia and America to support the Allied war effort. The Zionist leaders, he pointed out, were prepared to send ‘agents’ to Russia and America ‘to work up a pro-ally and especially pro-British campaign of propaganda among the Jews.’

The Declaration was issued the next day. To secure the results hoped for by the Foreign Office, Weizmann agreed to go first to Paris, then to the United States and then to Russia, to lead the campaign to rouse the pro-war elements among the Jewish masses in both countries. Vladimir Jabotinsky would go at once to Russia. ‘There is no question,’ Graham wrote to Balfour, ‘of the intense gratitude of the Zionists for the Declaration now made to them…. I believe that with their wholehearted cooperation with us may achieve valuable results.’ But on November 7, before Weizmann or Jabotinsky could set off, the Bolsheviks seized power in Petrograd and withdrew Russia from the war.

Publication of the Balfour Declaration had been delayed a week so that it could first be published in the weekly Jewish Chronicle on November 9. It was thus issued too late to affect the Bolshevik triumph. It did, however, encourage American Jews, especially those who had been born in Russia, to volunteer to fight in Palestine against the Turks as part of the British Army. Yitzhak Rabin’s father was one of them.

Churchill always regarded as a positive and immutable fact that the British government’s pledge to the Jews had been issued as a result of the urgent needs of the war. The fact that the Zionist Jews had been prepared to try to prevent Russia pulling out of the war meant much to him. As Minister of Munitions, he knew as well as anyone the dangerous situation to Britain, France and the United States on the Western Front as a result of Russia’s withdrawal from the war.

Following the Armistice, Lloyd George appointed Churchill Secretary of State for War. His new responsibilities included Palestine, then under British military administration. On 8 February 1920, as Soviet tyranny was being imposed throughout Russia, Churchill appealed to the Jews of Russia, and beyond, to choose between Zionism and Bolshevism. He did so in an article for a popular British Sunday newspaper. Of Zionism, he wrote: ‘In violent contrast to international communism, it presents to the Jew a national idea of a commanding character.’ It had fallen to the British Government, he explained, as the result of the conquest of Palestine, ‘to have the opportunity and the responsibility of securing for the Jewish race all over the world a home and a centre of national life. The statesmanship and historic sense of Mr. Balfour were prompt to seize this opportunity. Declarations have been made which have irrevocably decided the policy of Great Britain.’

The ‘fiery energies’ of Dr. Weizmann, Churchill added, ‘are all directed to achieving the success of this inspiring movement,’ and he went on to give his own Churchillian vision: ‘… if, as may well happen,’ Churchill wrote, ‘there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State under the protection of the British Crown, which might comprise three or four millions of Jews, an event would have occurred in the history of the world which would, from every point of view, be beneficial….’ A ‘negative resistance’ to Bolshevism was not enough, Churchill stressed. ‘Positive and practicable alternatives are needed in the moral as well as in the social sphere; and in building up with the utmost possible rapidity a Jewish national centre in Palestine which may become not only a refuge to the oppressed from the unhappy lands of Central Europe, but which will also be a symbol of Jewish unity and the temple of Jewish glory, a task is presented on which many blessings rest.’

In this article, Churchill also expressed his profound regard for an aspect of Judaism that had impressed itself upon him through his familiarity with the Old Testament. ‘We owe to the Jews in the Christian revelation,’ he wrote, ‘a system of ethics which, even if it were entirely separated from the supernatural, would be incomparably the most precious possession of mankind, worth in fact the fruits of all other wisdom and learning put together. On that system and by that faith there has been built out of the wreck of the Roman Empire the whole of our existing civilisation.’

In January 1921 Lloyd George appointed Churchill as Secretary of State for the Colonies, with special responsibility for the Palestine Mandate, which Britain had been awarded by the San Remo Conference in April 1920. To help Churchill in his task, a Middle East Department was set up in the Colonial Office, with Colonel T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) as Arab affairs adviser. Two years earlier, Lawrence had brought Weizmann to a conference at Akaba with Emir Feisal (son of Hussein, Sharif of Mecca), to ensure what Lawrence called ‘the lines of Arab and Zionist policy converging in the not distant future.’ Lawrence had also secured a pledge from Feisal that ‘all necessary measures’ would be taken ‘to encourage and stimulate immigration of Jews into Palestine on a large scale, and as quickly as possible upon the land through close settlement and intensive cultivation of the soil.’ In November 1918, on the first anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, Lawrence had told a British Jewish newspaper: ‘Speaking entirely as a non-Jew, I look on the Jews as the natural importers of western leaven so necessary for countries of the Near East.’

As Churchill began his work at the Colonial Office, Lawrence informed him that he had already concluded an agreement with Feisal whereby, in return for Arab sovereignty in Baghdad, Amman and Damascus, Feisal ‘agreed to abandon all claims of his father to Palestine.’ The Lawrence-Feisal agreement, with its Arab acceptance of the Jewish position in Palestine, was welcome news for Churchill. Since the French were installed in Damascus, and were not to be dislodged, Churchill favoured a scheme whereby Feisal would accept the throne of Iraq, and his younger brother Abdullah the throne of the largely desert Eastern Palestine – Transjordan – in return for Western Palestine – the whole area from the Mediterranean Sea to the River Jordan (today’s Israel and the West Bank) – becoming the location of the Jewish National Home.

To secure this outcome, Churchill prepared to set off from London for conferences in Cairo and Jerusalem. Before he left London, his senior Middle East Department adviser, John Shuckburgh, informed him that there was no conflict between Britain’s wartime pledges to the Arabs and to the Jews.

In 1915, in an exchange of letters between Sharif Hussein of Mecca and Sir Henry McMahon, the Arabs had been promised ‘British recognition and support for their independence’ in the Turkish districts of Damascus, Hama, Homs and Aleppo, each of which was mentioned in the promise, but which did not include Palestine. Two years later Britain had promised a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. If therefore, the land east of the Jordan became an Arab State, and the land west of the Jordan, up to the Mediterranean Sea, became the area of the Jewish National Home, Britain’s two pledges would be fulfilled.

To confirm that Britain had not promised the same area to both the Jews and the Arabs, the Middle East Department asked Sir Henry McMahon why, in his letters to Sharif Hussein in 1915, neither Palestine nor Jerusalem had been specifically mentioned as part of the future Arab sovereignty. McMahon replied that his reasons for ‘restricting myself’ to specific mention of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo were ‘(1) that these were places to which the Arabs attached vital importance and (2) that there was no place I could think of at the time of sufficient importance for purposes of definition further south of the above.’ McMahon added: ‘It was as fully my intention to exclude Palestine as it was to exclude the more northern coastal tracts of Syria.’ Western Palestine, from the Mediterranean to the River Jordan, had never been promised to the Arabs. There had been no double promise of the same land.

The Cairo Conference, with Churchill in the chair, began on 12 March 1921. The first decision made on Palestine was that Transjordan should be separated from Western Palestine, and that the Jews would be able to settle the land from the Mediterranean Sea to the River Jordan. In addition, Churchill explained, the presence of an Arab ruler under British overall control east of the Jordan would enable Britain to prevent anti-Zionist agitation from the Arab side of the river. Lawrence shared this view, pointing out that pressure could be brought on the proposed ruler in Amman, Emir Abdullah, ‘to check anti-Zionism’.

On 23 March 1921, Churchill travelled by train from Egypt to Palestine. At that time 83,000 Jews and 660,000 Arabs lived between the Mediterranean Sea and the River Jordan, in what was known as Western Palestine. No Jews lived east of the river. Churchill’s principal object in going to Jerusalem was to explain to Emir Abdullah that Britain would support him as ruler of the area east of the River Jordan provided that Abdullah accepted a Jewish National Home within Western Palestine, and did his utmost to prevent anti-Zionist agitation among his people east of the Jordan.

James de Rothschild, a leading British Jew and Member of the first Zionist Commission to Palestine, understood that by removing Abdullah from any control over Western Palestine, and giving him the area east of the Jordan, Churchill had ensured the survival of the Jewish National Home. Thirty-four years later he wrote to Churchill, thanking him, as he wrote, for the fact that in Jerusalem in 1921 ‘you laid the foundation of the Jewish State by separating Abdullah’s Kingdom from the rest of Palestine. Without this much opposed prophetic foresight there would not have been an Israel today.’

While in Jerusalem, Churchill visited the building site on Mount Scopus of the future Hebrew University, which opened four years later. ‘Personally, my heart is full of sympathy for Zionism,’ Churchill told the large Jewish gathering. ‘I believe that the establishment of a Jewish National Home in Palestine will be a blessing to the whole world, a blessing to the Jewish race scattered all over the world, and a blessing to Great Britain. I firmly believe that it will be a blessing also to all the inhabitants of this country without distinction of race and religion. This last blessing depends greatly upon you.’ ‘You Jews of Palestine,’ Churchill said, ‘have a very great responsibility; you are the representatives of the Jewish nation all over the world, and your conduct should provide an example for, and do honour to, Jews in all countries…. The hope of your race for so many centuries will be gradually realised here, not only for your own good, but for the good of all the world.’

On the morning of March 30 a delegation of senior Palestinian Arabs went to see Churchill at Government House in Jerusalem. They had sent him earlier a thirty-five page protest against Zionist activity in Palestine. In their memorandum, the Arabs sought to prove ‘that Palestine belongs to the Arabs, and that the Balfour Declaration is a gross injustice’. As for the Jewish National Home, and the very concept of Jewish nationalism, they informed Churchill: ‘For thousands of years Jews have been scattered over the earth, and have become nationals of the various nations amongst whom they settled. They have no separate political or lingual existence. In Germany they are Germans, in France Frenchmen, and in England Englishmen. Religion and language are their only tie. But Hebrew is a dead language and might be discarded’

The Arab memorandum continued: ‘Jews have been amongst the most active advocates of destruction in many lands, especially where their influential positions have enabled them to do more harm. It is well known that the disintegration of Russia was wholly or in great part brought about by the Jews, and a large proportion of the defeat of Germany and Austria must also be put at their door. When the star of the Central Powers was in the ascendant Jews flattered them, but the moment the scale turned in favour of the Allies Jews withdrew their support from Germany, opened their coffers to the Allies, and received in return that most uncommon promise’, the Balfour Declaration. ‘The Jew, moreover,’ Churchill was told, ‘is clannish and unneighbourly, and cannot mix with those who live about him. He will enjoy the privileges and benefits of a country, but will give nothing in return. The Jew is a Jew all the world over. He amasses the wealth of a country and then leads its people, whom he has already impoverished, where he chooses. He encourages wars when self-interest dictates, and thus uses the armies of the nations to do his bidding.’

The Arab memorandum concluded by asking Churchill that: ‘The principle of a National Home for the Jews be abolished.’ Churchill replied to the Palestinian Arab protests: ‘You have asked me in the first place to repudiate the Balfour Declaration and to veto immigration of Jews into Palestine. It is not in my power to do so nor, if it were in my power, would it be my wish. The British Government have passed their word, by the mouth of Mr Balfour, that they will view with favour the establishment of a National Home for Jews in Palestine, and that inevitably involves the immigration of Jews into the country. This declaration of Mr Balfour and of the British Government has been ratified by the Allied Powers who have been victorious in the Great War; and it was a declaration made while the war was still in progress, while victory and defeat hung in the balance. It must therefore be regarded as one of the facts definitely established by the triumphant conclusion of the Great War.’

‘Moreover,’ Churchill told the Palestinian Arab delegation, ‘it is manifestly right that the Jews, who are scattered all over the world, should have a national centre and a National Home where some of them may be reunited. And where else could that be but in this land of Palestine, with which for more than 3,000 years they have been intimately and profoundly associated?’

The Arab deputation withdrew, its appeal rejected, its arguments rebutted. A Jewish deputation followed in its place. Churchill told them: ‘I earnestly hope that your cause may be carried to success. I know how great the energy is and how serious are the difficulties at every stage and you have my warmest sympathy in the efforts you are making to overcome them. If I did not believe that you were animated by the very highest spirit of justice and idealism, and that your work would in fact confer blessings upon the whole country, I should not have the high hopes which I have that eventually your work will be accomplished.’

On his way back to Britain, Churchill visited Rishon Le-Zion. On approaching Rishon, he told the House of Commons a few weeks later, ‘we were surrounded by fifty or sixty young Jews, galloping on their horses, and with farmers from the estate who took part in the work.’ When they reached the centre of the town, ‘there were drawn up three hundred or four hundred of the most admirable children, of all sizes and sexes, and about an equal number of white-clothed damsels. We were invited to sample the excellent wines which the establishment produced, and to inspect the many beauties of the groves.’ Churchill then declared: ‘I defy anybody, after seeing work of this kind, achieved by so much labour, effort and skill, to say that the British Government, having taken up the position it has, could cast it all aside and leave it to be rudely and brutally overturned by the incursion of a fanatical attack by the Arab population from outside.’ It would be ‘disgraceful if we allowed anything of the kind to take place.’

What did Churchill see as the eventual evolution of the Jewish National Home? The answer came during a meeting in London on 22 June 1921, with all four Dominion Prime Ministers, from Canada, Newfoundland, Australia and New Zealand. At the meeting, the Canadian Prime Minister, Arthur Meighen, questioned Churchill about the meaning of the words ‘National Home’. Did they mean, he asked, giving the Jews ‘control of the Government’? To which Churchill replied: ‘If, in the course of many, many years, they become a majority in the country, they naturally would take it over.’

A Palestinian Arab delegation had arrived in Britain in July 1921, and taken up residence in London to lobby against any further Jewish immigration. To reassure Weizmann that British policy had not changed, Churchill, Lloyd George, and Balfour met Weizmann at Balfour’s house in London. According to the minutes of the meeting, Lloyd George and Balfour both agreed ‘that by the Declaration they had always meant an eventual Jewish State’. On the eve of his declaration, Balfour had told the War Cabinet, on 24 October 1917, that the declaration ‘did not necessarily involve the early establishment of an independent Jewish State, which was a matter for gradual development in accordance with the ordinary laws of political evolution.’ It was these ‘laws’ that Churchill was in the process of putting in place.

At the beginning of 1922, with the Balfour Declaration as their starting point, Churchill’s officials drafted a constitution for Palestine that would ensure that no Arab majority could stand in the way of continued Jewish immigration and investment. On 3 March 1922 the Arab Delegation, still active in London, held a meeting of its supporters at the Hyde Park Hotel in London to denounce Britain’s ‘Zionist policy’. Churchill was later sent a report of how the secretary to the delegation used language ‘about the necessity of killing Jews if the Arabs did not get their way’. In Cabinet, Churchill explained that he had decided to suspend the development of representative institutions in Palestine ‘owing to the fact that any elected body would undoubtedly prohibit further immigration of Jews.’

As Colonial Secretary, Churchill had one more battle to fight to preserve the Balfour Declaration and the continuance of Zionist activity in Palestine. His final task was to have the Mandate (with its pledge to continued Jewish immigration and an eventual Jewish majority) approved by the League of Nations. But the Balfour Declaration and its consequences were challenged in the House of Lords, and with them the crucial electrical and water power monopoly granted by Churchill to the Zionists in his first weeks as Colonial Secretary: the Rutenberg concession.

During the Lords debate, Lord Islington declared: ‘Zionism runs counter to the whole human psychology of the age.’ It involved bringing into Palestine ‘extraneous and alien Jews from other parts of the world’, in order to ensure a Jewish predominance. ‘The Zionist Home must, and does mean, the predominance of political power on the part of the Jewish community in a country where the population is predominantly non-Jewish.’

Another Peer, Lord Sydenham, insisted that the Mandate as being presented by Churchill to the League of Nations, ‘will undoubtedly, in time, transfer the control of the Holy Land to New York, Berlin, London, Frankfurt and other places. The strings will not be pulled from Palestine; they will be pulled from foreign capitals; and for everything that happens during this transference of power, we shall be responsible.’ When the vote was taken, the anti-Zionist Lords prevailed, with sixty voting against the Balfour Declaration, and only twenty-nine for it. Balfour’s promise to the Jews was in danger of not being fulfilled.

It fell to Churchill to attempt to reverse the House of Lords vote in the House of Commons, and to ensure, by a vote in the House of Commons, that the Zionist enterprise could go ahead under British stewardship. Before the debate, Churchill made enquiries that would free the Zionists from a particularly damaging Palestinian Arab complaint, that the Jewish Colonization Association had evicted Arabs from their lands in order to settle Jewish immigrants in their place. On July 3 the Colonial Office informed Churchill’s Private Secretary that ‘Mr Churchill may like to know, for the purposes of tomorrow’s debate, that this lie has been nailed to the counter.’ The land in question was ‘mainly swamps and sand dunes.’

The House of Commons debate on the Palestine Mandate took place on the evening of 4 July 1922. For the future of the Jewish National Home, and the emergence of Israel twenty-six years later, it was the testing time. For Churchill, it was one of the greatest parliamentary challenges of his career. His speech was a sustained defence of Britain’s pledge to Jewish national aspirations.

Dealing first with the Balfour Declaration, Churchill pointed out that: ‘Pledges and promises were made during the War, and they were made, not only on the merits, though I think the merits are considerable. They were made because it was considered they would be of value to us in our struggle to win the War. It was considered that the support which the Jews could give us all over the world, and particularly in the United States, and also in Russia, would be a definite palpable advantage.’

In defending Britain’s Palestine responsibilities, Churchill told the House: ‘We cannot after what we have said and done leave the Jews in Palestine to be maltreated by the Arabs who have been inflamed against them.’ Arab fears of being pushed off the land were ‘illusory’. No Jew would be brought in ‘beyond the number who can be provided for by the expanding wealth and development of the resources of the country. There is no doubt whatever that at the present time the country is greatly under-populated.’

In his first weeks as Colonial Secretary, Churchill had granted the Zionists control of the electrical power development of Palestine, the Rutenberg Concession. The House of Lords had specifically rejected this. In his speech, Churchill defended the concession, and Jewish economic involvement, which, he explained, would safeguard the Arabs against being dispossessed, for it enabled the Jews ‘by their industry, by their brains and by their money’ to create ‘new sources of wealth on which they could live without detriment to or subtraction from the well-being of the Arab population’.

Jewish investment, Churchill believed, would enrich the whole country, all classes and all races: ‘Anyone who has visited Palestine recently must have seen how parts of the desert have been converted into gardens, and how material improvement has been effected in every respect by the Arab population dwelling around’.

There was ‘no doubt whatever,’ Churchill insisted, that there was in Palestine ‘room for still further energy and development if capital and other forces be allowed to play their part.’ There was no doubt that there was room ‘for a far larger number of people, and this far larger number of people will be able to lead far more decent and prosperous lives.’ Apart from this agricultural work, this ‘reclamation work’ he called it, ‘there are services which science, assisted by outside capital, can render, and of all the enterprises of importance which would have the effect of greatly enriching the land, none was greater than the scientific storage and regulation of the waters of the Jordan for the provision of cheap power and light needed for the industry of Palestine, as well as water for the irrigation of new lands now desolate.’

Churchill then asked the House of Commons: ‘Was not this a good gift which the Zionists could bring with them, the consequences of which spreading as years went by in general easement and amelioration? Was not this a good gift which would impress more than anything else on the Arab population that the Zionists were their friends and helpers, not their expellers and expropriators, and that the earth was a generous mother, that Palestine had before it a bright future, and that there was enough for all? Were we wrong in … fixing upon this development of the waterways and the water power of Palestine as the main and principal means by which we could fulfil our undertaking?’

Before Churchill spoke, almost every speaker had been critical of granting so important an economic benefit to a Russian Jew. In response, Churchill told the House of Commons about Rutenberg and his financial backing: ‘He is a man of exceptional ability and personal force. He is a Zionist. His application was supported by the influence of Zionist organisations …. He produced plans, diagrams, estimates, all worked out in the utmost detail. He asserted, and his assertion has been justified, that he had behind him all the principal Zionist societies in Europe and America, who would support his plans on a non-commercial basis.’

It was the non-commercial aspect of the Rutenberg concession that Churchill stressed: ‘I have no doubt whatever, and, after all, do not let us be too ready to doubt people’s ideals, that profit-making, in the ordinary sense, has played no part at all in the driving force on which we must rely to carry through this irrigation scheme in Palestine. I do not believe it has been so with Mr Rutenberg, nor do I believe that this concession would secure the necessary funds were it not supported by sentimental and quasi-religious emotions.’

Churchill continued his speech with a defence of Rutenberg himself: ‘He is a Jew. I cannot deny that. I do not see why that should be a cause of reproach.’ It was imperative, Churchill told the Commons, that if the Balfour Declaration ‘pledges to the Zionists’ were to be carried out, the Commons must reverse the vote of the Lords. Churchill’s appeal was successful. Only 35 votes were cast against the Government’s Palestine policy, Balfour and Rutenberg, and 292 in favour. Churchill’s speech was a personal triumph: ‘one of your very best’ Lloyd George told him.

Following the Rutenberg Debate, Churchill submitted the terms of Britain’s Palestine Mandate to Parliament as a White Paper, known as the Churchill White Paper. ‘When it is asked what is meant by the development of the Jewish National Home in Palestine,’ the White Paper declared, ‘it may be answered that it is not the imposition of a Jewish nationality upon the inhabitants of Palestine as a whole, but the further development of the existing Jewish community, with the assistance of Jews in other parts of the world, in order that it may become a centre in which the Jewish people as a whole may take, on grounds of religion and race, an interest and a pride. But in order that this community should have the best prospect of free development and provide a full opportunity for the Jewish people to display its capacities, it is essential that it should know that it is in Palestine as of right and not on sufferance. That is the reason why it is necessary that the existence of a Jewish National Home in Palestine should be internationally guaranteed, and that it should be formally recognized to rest upon ancient historic connection.’

The Churchill White Paper was approved by the League of Nations in Geneva on July 22. Four days later, Weizmann wrote to him: ‘To you personally as well as to those who have been associated with you at the Colonial Office, we tender our most grateful thanks. Zionists throughout the world deeply appreciate the unfailing sympathy you have consistently shown towards their legitimate aspirations and the great part you have played in securing for the Jewish people the opportunity of rebuilding its national home…’

On hearing of the League of Nations’ approval of Churchill’s White Paper, one of the leading Zionist thinkers, Ahad Ha’am, then living in the Jerusalem garden suburb of Talpiot, told those who were with him when the news arrived: ‘Akhshav anachnu be’artzenu’: ‘Now we are in our own land.’

The Balfour Declaration and the Jewish National Home provisions of the Mandate were intact. As a result of Churchill’s commitments, 400,000 Jews entered Palestine between 1922 and 1940, bringing the population to almost half a million within twenty years. Two future British governments, Ramsay Macdonald’s in 1929 and Neville Chamberlain’s ten years later, were to make grave inroads into the Balfour Declaration and Churchill White Paper commitments to the Jews. But, thanks first to Balfour and then, predominantly, to Churchill – to both his practical and his emotional commitment to the Zionists and his 1922 White Paper – the Jewish National Home continued to be built, and was strong enough, numerically, economically and institutionally, to emerge into statehood in 1948.