The August 14th edition of the BBC World Service radio programme ‘The History Hour’ included an item (from 09:34 here) that was introduced by presenter Max Pearson using dubious linkage.

“While the last acts of the Cold War were being played out towards the end of the 1980s, the unavoidable consequence in the Middle East was renewed uncertainty and tension. And you couldn’t necessarily escape just by moving away from the region. In 1987 the acclaimed Palestinian cartoonist Naji al Ali was gunned down in London. His attackers have never been identified. Naji al Ali’s cartoons were famous across the Middle East. Through his images he criticised Israeli and US policy in the region but unlike many, he also lambasted Arab despotic regimes and the leadership of the PLO. Alex Last has been speaking to his son Khalid about his father’s life and death.”

Listeners then heard an item that had been broadcast the previous week in the BBC World Service radio programme ‘Witness’ and was discussed here. At the close of that interview, Pearson continued the item (from 18:52) as follows:

Pearson: “Khalid al Ali was talking to Alex Last about his father the cartoonist Naji al Ali whose murder in London thirty years ago serves to highlight the potential dangers of simply trying to portray the world how one sees it. Those dangers were more recently illustrated by attacks on the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and the threats to Danish interests after the Jyllands-Posten newspaper published cartoons depicting the prophet Mohammed. I’m joined now by the cartoonist Martin Rowson whose work appears in, among other publications, the Guardian here in Britain. Ehm…Martin; is yours a dangerous profession?”

Rowson “It always has been and always will be because the whole purpose of satire is to tell truth to power while laughing at power at the same time. And actually the laughter is always more dangerous than the truth because they cannot stand the idea that we’re laughing at them in their grandeur and the rest of it.”

Rowson later went on to say:

Rowson: “I receive death threats on a regular basis but I always work on the basis they don’t count if they come by email. It’s just somebody who has been so utterly disgusted and shocked – on somebody else’s behalf invariably – so deeply offended that they want to do something far more offensive than laughing at somebody in power and kill me. And it’s bizarre that people get so incensed by this stuff.”

Pearson: “Well you use the phrase ‘speak truth to power’ but truth is very subjective. Is speaking truth to power what the cartoonist generally does or is it that he or she is simply being rude about people or ideas with which he or she does not agree?”

Rowson: “I think that’s part of it but mostly it’s the idea of mocking the powerful. That’s where the danger comes in because the powerful and their supporters cannot endure the idea of mockery because mockery is the most powerful weapon against them. […] So any despotism – be it secular or religious – will defy people not to laugh at the absurdities inherent in them. And if you do laugh at them, it’s unendurable but also powerful.”

Pearson: “But how, looking back over history, have the red lines – the lines in the sand, so to speak – shifted? […] today there certainly will be people who will think very carefully about depicting images of the prophet Mohammed in a mocking way because of the potential consequences.”

Rowson: “Well that’s certainly true. And after the Charlie Hebdo killings I proposed to the Guardian that I do a cartoon of the prophet Mohammed with his head in his hands, so you wouldn’t see his face, wearing a ‘not in my name’ T-shirt. And they decided that actually that was too dangerous for Guardian staff working in the Middle East. And I respect that decision. Actually it was too dangerous for me as well. I’d have had to go into hiding which is preposterous but it actually gets to the point where you’re not allowed to say anything about anything.”

Then, in the very next breath – and as though it were comparable to murders, terrorism, death threats and violence over cartoons deemed offensive by some Muslims – Rowson went straight on to the topic of entirely non-violent criticism from a particular group.

Rowson: “A few years ago I just stopped doing cartoons about Israel because I was fed up of every time I did a cartoon about Israel getting literally thousands of emails accusing me of being a worst anti-Semite than Hitler, which is just not true. But everybody will use this excuse of being offended to shut up the person they’re engaged in an argument with.”

While Martin Rowson is rightly protective of his own freedom to ‘speak truth to power’ (as long as it’s not Muslim power), he is obviously less keen on the idea of anyone else criticising the power that he holds as a widely published cartoonist influencing public opinion. In the past Rowson has accused “the Israel lobby” of using antisemitism (i.e. the Livingstone Formulation) to try to silence his “criticism of their brutally oppressive colonialism”.

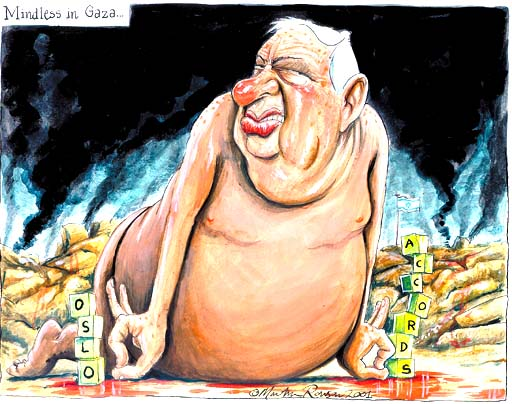

Here is a cartoon Martin Rowson drew in April 2001, as the second Intifada raged:

This is a Martin Rowson cartoon from July 2006 relating to the second Lebanon war that began when Hizballah conducted a cross-border raid and fired missiles at Israeli civilian communities:

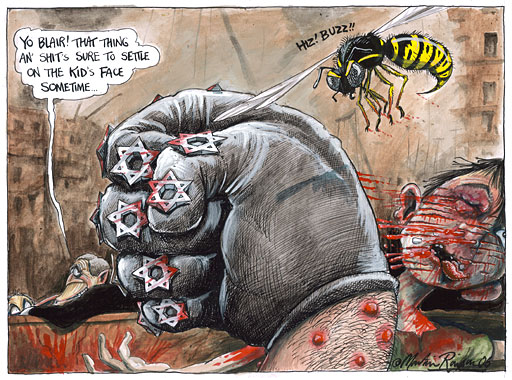

These are cartoons published by Rowson during Operation Cast Lead in 2009 after thousands of missile attacks had been launched against Israeli civilians by Hamas:

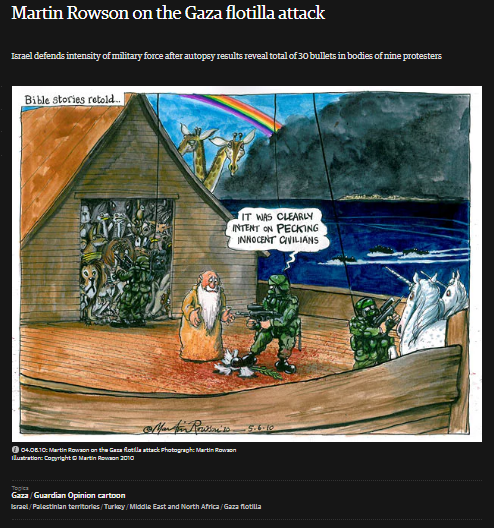

Here is Rowson’s take on the 2010 ‘Mavi Marmara’ incident.

This is a Rowson cartoon published three days after the commencement of Operation Protective Edge in response to 131 missile attacks on Israeli civilians in the preceding days.

Max Pearson, however, had nothing to tell listeners about Rowson’s trite, monochrome, one-sided Israel-related cartoons or why some people might find them objectionable. Instead – immediately after Rowson’s remarks about “getting…emails” he said:

Pearson: “So almost by definition – going back to my original point – the political cartoon is dangerous.”

Rowson: “Yeah. It’s meant to be dangerous. It’s a sort of point of licence to anarchy.”

Pearson closed by thanking the “esteemed cartoonist” and BBC World Service audiences went away with the impression that indignant e-mails carry the same weight and importance as the terrorist murders of cartoonists who drew Mohammed.

Related Articles:

More narrative-driven ‘history’ from the BBC World Service

Did CiF Watch “browbeat” Guardian cartoonist Martin Rowson into submission? (UK Media Watch)

Martin Rowson: Israel lobby uses antisemitism to silence critics of Zionist brutality (UK Media Watch)